A new office in the Department of Energy holds immense promise for closing the gap for clean energy demonstrations.

Photo by JSquish via Wikimedia Commons

The Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) could represent a unique opportunity to help new, climate-friendly energy sources prove their potential, so that communities and other stakeholders can see them working in action. Good Energy Collective is excited that the Biden administration is standing up OCED and hopes to see the office take up our working group’s recommendation to conduct regular stakeholder engagement with overburdened and underserved communities. To increase equitable access to clean energy, DOE should make sure that disadvantaged communities know about opportunities related to OCED; receive assistance to participate, if needed; and can shape and benefit from the office’s projects.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s new Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations is a tremendous step forward for innovation and must become a permanent fixture in the federal structure. DOE needs time right now to build up the new office systematically, and over the next few years its funding must grow rapidly, so that it can drive a steady stream of innovations ready to be scaled up nationally and globally. We have provided two sets of recommendations to this new office, laying out implementation strategies and considerations to chart a course for OCED’s success.

A Star Is Born

President Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA, known colloquially as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) in November 2021. Contained within its thousands of pages is an important new clean energy innovation organization: the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) within the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

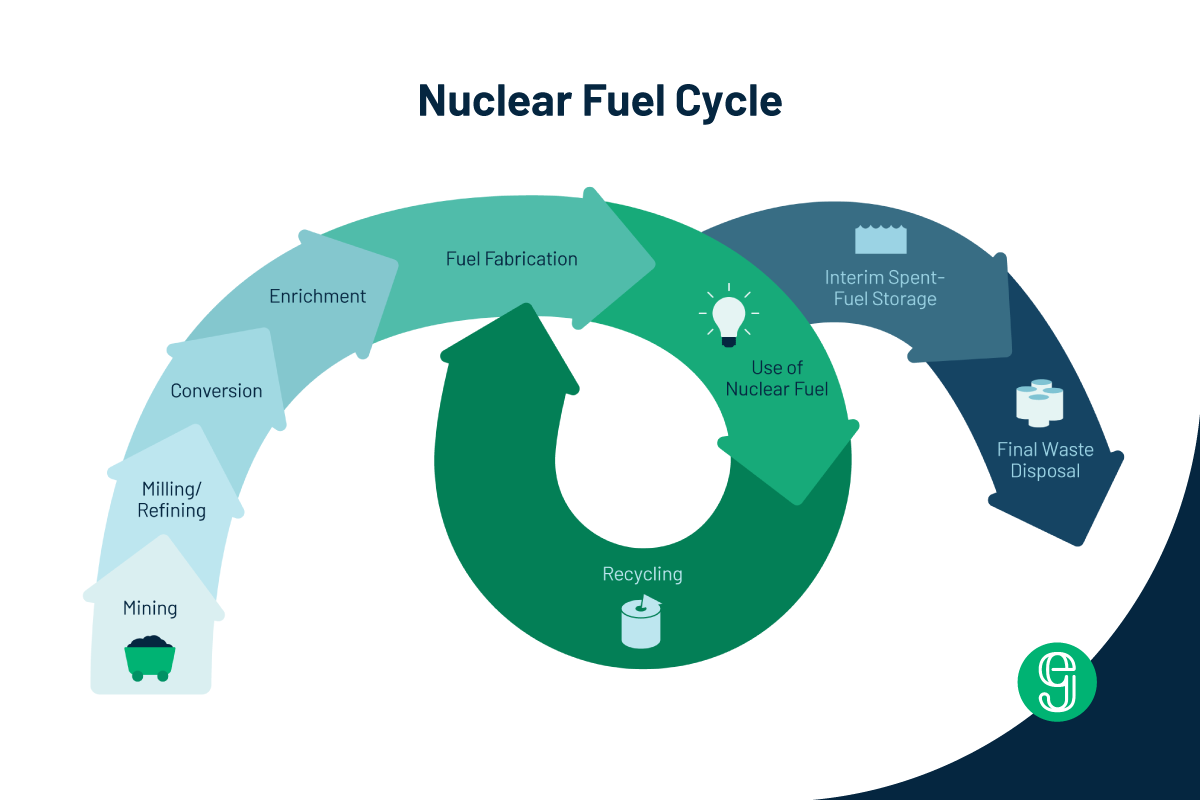

Funded at $21 billion over the next five years, OCED could dramatically accelerate the pace of deployment of key low-carbon technologies like clean hydrogen, advanced nuclear energy, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) from industrial facilities and power plants. Demonstrations supported by OCED will receive resources and financial, market, and program management expertise that will help bring innovative clean energy technologies from R&D to the commercial market. Furthermore, demonstrations will provide critical information needed by stakeholders, especially the private sector, to move a technology to a commercial application.

We welcome OCED’s creation and are enthusiastic about the thoughtful and strategic steps that DOE has taken so far to establish it. However, DOE should take note of its past failures and successes to build a new strategy for managing large-scale demonstration projects. That means that the new office must be focused on managing risk and solving market and customer problems rather than on scientific achievements or short-term political wins. It will need to gain public trust and engage in a continual dialogue with its many stakeholders. A group of think-tanks and non-governmental organizations, including those that we represent, are working to support this effort in order to make OCED the success story the world needs it to be. Every effort should be made by both OCED and the Applied Program offices to ensure a smooth transition for any projects moving into OCED.

This post briefly explains where OCED came from and offers a vision of where it should go in the future. Along the way, we share two sets of recommendations that our working group developed and provided to DOE leadership. A key objective as we look ahead is to equip policymakers and DOE with the information needed to build a firm foundation for OCED. Significant progress has already been made, but it will take years of consistent funding for OCED to develop the capabilities and expertise it needs and to refine a market-oriented framework for the demonstration of new technology.

Congress must therefore continue to invest in energy demonstration projects and the expertise required to manage those projects to bolster OCED’s current activities and sustain its momentum once OCED’s initial funding under the IIJA runs out. If future funding wanes, OCED’s progress will be squandered, as will be the United States’ opportunity to demonstrate key innovations and compete globally.

The Demonstration Gap

Demonstration is a key stage in the innovation process. The International Energy Agency (IEA) defines it as the “operation of a prototype ... at or near commercial scale with the purpose of providing technical, economic and environmental information.” Without such information, potential investors will lack confidence in a new technology’s potential rate of return. As a result, investors often direct their money elsewhere, creating a demonstration gap which is particularly wide for capital-intensive energy technologies like new kinds of power plants and factories. In fact, the lack of public funding to demonstrate these technologies on a large scale has slowed their progress to date. A comprehensive review of demonstration projects across eight sectors over the last half century by Gregory Nemet of the University of Wisconsin and his colleagues found that public funding was often essential to get these major innovations across this “valley of death.”

In the past, the U.S. federal government has provided funding in fits and starts for first-of-a-kind (and sometimes, second, third, and “nth” of a kind) energy demonstration projects, in some cases creating entire industries through its support. Civilian nuclear power, which provides the bulk of low-carbon electricity today, benefited from such funding in the 1950s and 1960s. The American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) of 2009 provided a more recent burst of support, investing about $4.5 billion to demonstrate energy storage, smart grid, and carbon capture and storage technologies, to name just a few. However, until the passage of the IIJA a few months ago, no new federal money had gone toward large-scale energy demonstration projects for more than a decade.

Unfortunately, DOE’s management of large-scale projects was inconsistent, sometimes haphazardly expedited, and even politically influenced. While many ARRA demonstration projects were well-managed and produced valuable information, several large projects were not completed due to funding and timing constraints. Additionally, little was done with the information gathered from these incomplete projects to advance innovation and commercialization of these technologies. Once the economic emergency caused by the 2008 financial crisis eased, familiar Washington budget battles resumed, and the skeptics of a demonstration role for DOE were able to limit its funding to conventional research and development (R&D) rather than demonstration in the 2010s.

Closing the Gap: Consensus Builds

Even as energy demonstration projects were largely excluded from federal programs, interest grew in exploring ways to improve their management. In 2009, the Breakthrough Institute and Third Way advocated for a “National Institutes of Energy” modeled on the National Institutes of Health, that aimed to better bridge the gap between R&D and commercial application. This idea was revived by Bill Gates in his 2020 article on how the U.S. can lead the world on climate change innovation. In 2011, MIT’s John Deutch, who served as Deputy Secretary of Energy under President Carter, revived a proposal to create an independent government corporation for this purpose. George Mason’s David Hart (a co-author of this post) and MIT’s Richard Lester put forward a regionally-organized approach for initiating and managing large-scale demonstrations.

Then, in 2017, Joe Hezir, former Chief Financial Officer of DOE, recommended establishing an independent demonstration project management office within DOE. The Energy Futures Initiative, where Hezir is currently a principal, and IHS Markit included the proposal in their 2019 Advancing the Landscape of Clean Energy Innovation. The American Energy Innovation Council, a group of CEOs assembled by the Bipartisan Policy Center, consistently advocated for larger investments in and new ways of managing demonstration projects in its annual reports. David Hart and Robert Rozansky of Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) developed Hezir’s idea and its rationale in greater detail in a 2020 report entitled, “More and Better: Building and Managing a Federal Energy Demonstration Portfolio.”

The main rationale behind OCED’s creation is that large-scale demonstration project management requires a different skill set than R&D program management, which is the bread and butter of DOE’s applied energy offices. While every technology has unique attributes – nuclear energy is very different from hydrogen production – many project requirements, ranging from keeping construction on schedule to managing complex financial packages, are consistent across all demonstration projects. Under ARRA, the applied energy offices managed demonstration projects related to their R&D programs, meaning that these projects were solicited, evaluated, and selected using disparate processes, as were successes and termination decisions. Under a unified OCED, and once the capacity to manage demonstration projects is built, these processes will become more uniform and the Office’s much broader and more diverse set of projects can be managed as a portfolio, mitigating key risks, and strengthening the prospects for follow-on commercialization of the best-performing technologies.

From Idea to Reality: Congress Fills the Gap

With over a decade of failed energy bills in Congress and pressure for more innovative demonstration programs building, Congress enacted and President Trump signed into law the bipartisan Energy Act of 2020. The new law laid the groundwork for OCED by authorizing demonstration programs across a range of clean energy technologies. Then the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee adopted a bipartisan bill that authorized a version of OCED, articulating the need for centralized management, clear milestones and evaluation criteria, and increased capacity to demonstrate large-scale energy projects. Building on the Energy Act, the Biden administration included a request for OCED in its fiscal year 2022 Budget Request. Appropriations subcommittees in the House and Senate both included the office in their DOE funding bills for that year.

Congress made the idea of a centralized management office for large-scale demonstrations a reality by including OCED in the 2021 bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The IIJA provides both an authorization that lays out OCED’s main responsibilities and a five-year budget, which is detailed here.

DOE's implementation of the legislation – above all, how projects are selected and carried out – will determine whether the theory set forth in the various reports that led to its creation will be validated in practice. Responding to this opportunity and challenge, our working group convened to engage with DOE and to provide recommendations based on our collective research and experience.

After several months of deliberation and outreach with other stakeholders, the working group offered DOE eight management principles and subsequent implementation recommendations in October 2021:

- Focus on very large and complex projects.

- Hire a mix of experts drawn from the private sector and DOE career employees.

- Solicit, select, and manage demonstration projects – own the full lifecycle.

- Be technology-inclusive and cover all major GHG-emitting emission sectors.

- Engage a diverse set of stakeholders across numerous sectors, including, disadvantaged and frontline communities.

- Make collaboration and coordination with the private sector be a priority.

- Coordinate with the rest of DOE, particularly the technology-specific program offices.

- Develop transparent selection processes based on merit.

The full recommendations can be found here.

DOE formally established OCED in December 2021. After consulting with its leadership, our working group prepared a second set of recommendations on three topics, which we shared with DOE in February 2022:

- Measure success at the portfolio-level and continually manage risk over the course of each project’s progression.

- Require project proposals to include a plan for stakeholder engagement and consider it when evaluating them.

- Expand participation by supporting pre-proposal development in areas like market, customer, and community analysis as well as technology risk and performance.

The full recommendations can be found here.

The Future of OCED: No More Castles in the Sky

The creation of OCED is a tremendous step forward for innovation, and we all have a stake in ensuring this progress is not wasted or undermined by future funding shortfalls. The climate and clean energy challenge is huge, complex, and multi-faceted. A pipeline of emerging technologies that are not yet ready to be demonstrated must continue to have a path to maturity in the late 2020s, 2030s, and beyond. For these reasons, OCED must become a permanent fixture in the federal structure.

To achieve this objective, DOE must take the time to create a strategic and transformational framework, build and strengthen its federal workforce with new talent, and not be pressured to spend money under rapid timelines. As OCED builds its foundation and demonstrates success, consistent and regular appropriations to maintain DOE’s new capabilities must grow rapidly and in proportion to capital costs of large-scale demonstrations.

In the near term, OCED will be a success if the large-scale demonstration activities funded in IIJA lead to a steady stream of advanced clean energy technologies that are scaled up and deployed for widespread use nationally and globally. Long-term, OCED will use its new capabilities to ensure the emerging and advanced clean energy technologies of the future get the same benefit, rather than go over a fiscal cliff. OCED has been given an extremely big and difficult job, but we believe that it can succeed.

.png)

.png)

%252520(1200%252520%2525C3%252597%252520800%252520px).png)