An illustration of our understanding of the concerns Americans have about nuclear energy and actions that can address them

"March For Climate Justice NYC" on September 20, 2020. Photo credit: Ron Adar via Shutterstock.

Click here to download the pdf of the policy memo.

Introduction

Communities in the U.S. are facing increased likelihood of extreme weather and sea level rise due to global increases in temperature, with socially vulnerable populations projected to experience some of the worst impacts. The human and financial costs of domestic natural disasters and extreme weather continue to grow. Climate science has shown that countries like the U.S. must significantly reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate the most severe effects of climate change.

Like renewables, nuclear energy produces large amounts of low-carbon power. Today, nuclear provides more than half of the country’s low-carbon electricity. Its emissions intensity is on par with hydropower and wind energy. And global nuclear generation may need to double by mid-century if the world is to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency.

But a lot of Americans harbor reservations about the use or expansion of nuclear energy: U.S. adults remain less supportive of federal actions to encourage nuclear energy than other clean energy technologies, and their outright support for nuclear continues to hover around 50%. The industry’s historical connections to atomic weapons production, unresolved legacy contamination, high-profile domestic and international accidents, instances of corruption, and missteps in community engagement have increased Americans’ skepticism of nuclear energy as a solution for climate change or local electricity production.

Various demographics also perceive environmental and technological risks differently depending on how they think about the world. Research has shown that white people and men tend to value institutional hierarchy and individual freedom, and have significantly higher tolerance for risks than others. These groups have dominated the realms of nuclear policy decisions since the beginning of the use of nuclear for weapons or energy. In contrast, women and people of color often hold more communitarian and egalitarian worldviews that are correlated with greater concerns about risk. Polling bears out the gender differences in support for nuclear technology: In a 2021 survey Good Energy Collective conducted with Data for Progress, more than double the number of men than women thought favorably of advanced nuclear energy (56% of men vs. 27% of women). While white men have driven much of the decision-making around nuclear, Indigenous and minority groups have been regularly marginalized, including through displacement for weapons production and uranium mining and milling facilities and through radiological experiments that involved Indigenous and people of color. Already-vulnerable communities may naturally be more risk-averse toward nuclear development over concerns about local land or water pollution.

Many environmental justice and climate advocates hold concerns about nuclear for these and other reasons. In 2020, over 100 environmental groups registered their disapproval of congressional legislation to create a Strategic Uranium Reserve and support nuclear energy, which they called “too dirty, too dangerous, too expensive, and too slow to address climate change” and “rooted in environmental injustice and human rights violations.” In 2021, the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, composed of leaders in the environmental justice movement, included nuclear power procurements in their list of federal projects that fail to deliver community benefits.

Other progressives and climate activists are willing to consider nuclear energy in the face of climate change—as long as its legacy issues are addressed. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) has said in 2019 that her visionary Green New Deal “leaves the door open to nuclear” as long as communities can provide input and the technology is tested. Progressive polling and policy think tank Data for Progress’ Julian Brave NoiseCat cited the industry’s “horrific history of polluting indigenous communities” domestically, while also supporting nuclear as a tool of emissions reduction. Other prominent environmental activists, including Jane Fonda and Greta Thunberg, have become more supportive of the technology in light of the climate crisis.

As early as August 2020, Good Energy Collective’s co-founders helped elevate a discussion around how to move nuclear energy forward in ways that center environmental justice and support frontline communities. We recommended staffing up the Office of Nuclear Energy with those who commit to an interdisciplinary approach; increasing funding for social science research into nuclear; supporting communities facing coal plant retirements with nuclear energy; and identifying opportunities for communities harmed from previous nuclear fuel cycle activities. Simultaneously, the Biden team worked with progressive Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and other environmental leaders on the left to articulate an environmentally-just climate plan that supported advancements in nuclear and other technologies and focused on protecting environmental justice communities from pollution. Under the Justice40 initiative, federal agencies have started to track investments and ensure that at least 40% of the benefits from federal environmental investments flow to overburdened and underserved areas. But tracking the benefits, while an important step, is only one component of successfully embedding justice in federal programs and activities that support communities, nuclear energy, and environmental clean-up.

For nuclear energy to play an increasing role in domestic climate action, U.S. industry players and the federal government need to recognize and respond to the causes of concern and opposition to this technology. The people developing and promoting the technology first must commit to addressing the legacy issues that caused the environmental movement to reject nuclear energy to begin with. The urgency of the plight of environmental justice communities still facing air and water pollution from fossil fuels, and the necessity of climate action to ensure a livable world, require immediate action.

This interim roadmap illustrates our current understanding of the reasons why Americans continue to have rational concerns about nuclear energy, and of examples of some of the steps that the federal government and the nuclear industry can take to address them. It reflects Good Energy’s conversations to date with community-facing environmental justice, climate, and nuclear organizations and our own research. But it’s only a start: We continue to learn from and respond to communities’ preferences regarding their energy mixes and the processes taken to achieve them. We are in the early stages of a long journey toward nuclear justice.

If you work with a U.S.-based environmental justice or climate organization and would like to join us on this journey, please reach out at hello@goodenergycollective.org to set up an introductory meeting with our team.

What Is Nuclear Justice?

President Joe Biden entered into office with a focus on advancing environmental justice, as well as building out significant low-carbon energy, including nuclear. For over 20 years, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has defined environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” For many progressives, the nuclear sector in the U.S. has neither fairly treated nor meaningfully involved all people: Communities—predominantly Indigenous—continue to face legacy pollution from the domestic uranium industry; utilities and developers have historically beaten down community concern about new nuclear plants; and the federal government still hasn’t met its statutory requirement to move nuclear waste out of communities that never agreed to host it indefinitely. These errors have resulted in comparative public mistrust in nuclear energy compared to other low-carbon energy technologies.

In our understanding, nuclear justice is a combination of restorative, procedural, and distributive justice activities that center communities’ energy, economic, and environmental needs and desires in the decision-making process for nuclear energy projects. It is a recognition that domestic federal and business choices about nuclear have often been unjust, inequitable, or unconcerned with protecting disadvantaged groups, empowering democratic processes, or uplifting underserved communities. And it’s a demand for improvements in these areas before, during, and once new nuclear fuel cycle facilities and reactors are built, so that nuclear energy can play a meaningful role in producing low-emission energy and reducing carbon emissions in an energy system that puts people first.

Restorative Justice

Restorative justice is an approach to conflict resolution that gives all impacted stakeholders the ability to talk about the injustice they have experienced and determine the recourse. It has roots in approaches by North American and New Zealand native communities, Mennonites, and other religious practitioners. In the environmental context, we interpret it to mean holding polluters accountable, ensuring clean-up happens, and seeking and incorporating affected communities’ wishes before and during remediation.

For nuclear, then, restorative justice places an obligation on the part of the federal government and nuclear industry players who knowingly harmed communities through nuclear weapons production and testing and uranium extraction to work with these communities toward restitution. It recognizes that the impacts of using and testing nuclear weapons transcend national boundaries, span decades, and can result in multigenerational health impacts.

The entanglement of nuclear technology development and human oppression and exploitation date back to the early 1900s, when Belgium colonized the Congo for mining of natural resources, which led to the discovery of very pure uranium. For decades, the Belgian-owned mine forced the local Black population to dig uranium at Shinkolobwe in support of atomic weapons development. Local communities saw none of the profits and received no personal protective equipment, medical care, or education about the long-term health effects of radiation contamination. As U.S. nuclear policy and technology shifted towards a fully domestic nuclear fuel cycle, the government and industry partners used colonial violence against the Navajo people, or Diné, to seize control over Diné Bikéyah, the sacred lands of the Navajo people. Exploitation, discriminating policies, and resulting economic factors drove Indigenous men from the Navajo Nation to work in the mines—without provisions for personal protective equipment, which exposed their families to radioactive contamination on their clothes. The Indigenous communities often built their homes with material from mine sites or drank from contaminated water sources, and never received information about the dangers associated with uranium mining. In 1979, a dam on Navajo land at a uranium processing site broke, spilling into the Puerco River “the largest release of radioactive materials” domestically to date.

These historical harms—and present-day efforts by industry to reopen mines that Indigenous communities oppose—are a primary reason why progressives and environmental justice advocates distrust nuclear. Indigenous and other frontline communities are still dealing with the long-term negative impacts from the nuclear industry from mining and milling and weapons testing, including the largest radioactive spill in the U.S. at Church Rock. At the same time, investor and mining interests are swelling around reviving domestic uranium extraction, frustrating tribes like the Havasupai, which opposes the restart of local uranium mining.

Although the production of nuclear weapons was separate from commercial nuclear energy, the legacy issues of the two industries are often muddled in the public’s thinking about “nuclear.” The history of nuclear weapons production in the U.S. has left many contaminated sites, such as Hanford in Washington state and Rocky Flats in Colorado.

Remediating Legacy Waste Sites

The U.S. Department of Energy takes custody of uranium mill waste sites, and many abandoned uranium mines and mills are on the Environmental Protection Agency’s lists of sites that qualify for federal remediation support. But many communities—and tribes in particular—are still straddled with unremediated uranium mines. The Navajo Nation alone contains over 500 abandoned uranium mines. Other tribes, such as the Lakota, also have unreclaimed legacy uranium sites on their lands. These sites deserve comprehensive clean-ups conducted with the input of local tribes and other communities.

Procedural Justice

Procedural justice ensures that decisions follow equitable processes which include all affected stakeholders. Achieving the “meaningful engagement” tenet of environmental justice is a matter of procedural justice. Nuclear energy has a checkered history when it comes to this type of justice—not least because many U.S. nuclear plants were sited while the Atomic Energy Commission both regulated and promoted nuclear energy. Developers and utilities determined where they wanted to build nuclear reactors before announcing it publicly. Congress’ passage of the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969 and the formation of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1974 gave the public new opportunities to learn about and challenge the siting of nuclear reactors, but communities still felt underserved by the processes. Developers then spent a lot of money battling lawsuits that challenged their projects, spiking the overall cost of reactor builds and stoking acrimony among developers toward intervenors. That practice, and a sense among the public of a predetermined outcome in favor of the government and utilities’ wishes to build the plants, sowed mistrust in the process. Interventions come at a high cost for under-resourced communities seeking more information into the proposed reactors.

One of the most prominent examples of procedural injustices in the U.S.’ nuclear’s history was the effort to site a federal nuclear waste repository. While the U.S. Department of Energy was considering several potential sites for nuclear waste storage in the early 1980s, a 1987 congressional amendment to the Nuclear Waste Policy Act narrowed the consideration to only one site: Yucca Mountain in Nevada. The site was chosen partly because Nevada lacked political power at the time. Decades of opposition to the project led to its effective cancellation when the government defunded the project in 2010.

That includes the Western Shoshone Nation, which has never backed the siting of a permanent nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain but whose opposition the government has not credibly taken into account. The U.S. government also has a legal responsibility to support tribal self-government and economic prosperity, but it does not consistently meet its requirement to support tribal sovereignty. The U.S. Government Accountability Office has identified many shortcomings with federal agencies’ government-to-government consultation with tribes on infrastructure projects.

Involving local communities and tribal nations as equal partners early in the siting process serves utilities and developers’ interests as much as the public interest. Ultimately, public opposition resulted in the cancelation of multiple U.S. reactor projects, such as one in Shoreham, New York. More equitable siting practices could support better outcomes for communities and for industry.

A procedurally just approach to nuclear will ensure that diverse and representative stakeholders are able to participate in each step of decision-making processes and can grant revocable consent or opposition to new projects that may affect their health and environment. In the context of nuclear energy, it is critical that communities have access to the information, resources, or experts they need to weigh the costs, safety risks, and benefits of a particular project.

Finally, the cost of nuclear power often arises in our interviews as a reason to oppose nuclear power. While the issue of cost may not appear to qualify as a justice issue, the lack of transparency and public consultation in large utility decisions around investment could be seen as a procedural injustice. In the 1970s, many utilities predicted that demand for electricity would continue to grow and accordingly made large investments in nuclear. When demand for electricity crashed in the 1980s and 1990s, they mothballed many of these projects, and the investments looked like boondoggles.

More directly, a 2020 bribery scandal in Ohio spotlit the $60 million that a utility gave toward a fund controlled by the state House speaker in exchange for passing a nuclear bailout bill. This sort of corruption is not unique to nuclear, but large infrastructure bills do open opportunities for corruption and generally contribute to a feeling that nuclear is anti-democratic.

Siting Plants Using Consent-Based Decision-Making

Industry players should move past a “decide-announce-defend” siting model to one that earns local consent. That process will require utilities and/or developers or federal partner agencies to hold meetings with potential community co-developers from project conception through operation—and respect communities whose stakeholders say “no” to nuclear.

Storing and Disposing of Nuclear Waste

While military waste is still being dealt with at a handful of sites including Hanford in Washington state and Savannah River in South Carolina, civilian nuclear waste is located at 76 sites in 34 states across the U.S. The challenge is political and procedural, but not technical: Much of this waste now sits in dry cask storage until the U.S. government meets its legal obligation to oversee nuclear waste and, eventually, develop a permanent repository. This prolonged state of limbo, in which communities are hosting the waste without their consent or a long-term plan, has resulted in doubt and mistrust in nuclear waste management.

For advanced nuclear technologies to contribute to the climate response, the government will need to commit to implementing nuclear waste management that takes local and state interests into account. To that end, the Biden administration has resumed a consent-based approach to siting nuclear waste from around the country—a process that was recommended and initiated during the tenure of President Barack Obama. The nuclear waste siting processes followed in Sweden, Finland, and Canada reflect positive, instructive approaches to community outreach and engagement.

Easing Public Participation

Calls are growing for improved opportunities for public engagement with federal nuclear regulators about reactor and mining projects. Recently, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission recognized it is likely time to update its policies on environmental justice, which the agency has not updated since 2004. From 2021-22, it undertook a systematic assessment of how it approaches environmental justice, taking public input and making suggestions to the commission, which has not yet acted on the recommendations. And in October 2022, Rep. Mike Levin (D-CA) introduced legislation that would create an Office of Public Engagement and Participation at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to help the public participate in NRC proceedings, including submitting comments and participating in hearings and interventions.

Engaging Stakeholders

In July 2022, the Department of Energy issued general guidance to its offices for how to implement the Justice40 initiative. Included in that guidance is a new requirement for applicants seeking Energy Department funding to create a Stakeholder Engagement Plan. The plan is to outline how the applicant intends to engage local stakeholders in the planning process for their proposed project. For its part, the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management has released a more comprehensive public guide for what applicants should include in their stakeholder engagement plans.

Distributive Justice

Distributive justice in nuclear energy is a tangled problem. At first glance, it may seem ideal to make sure that the burdens of industrial infrastructure, like nuclear facilities, should entirely avoid disadvantaged communities. However, this approach risks excluding these communities from the potential economic and social benefits that these projects provide. In existing reactor communities, nuclear power plants have carried immense economic benefits, supporting 20-30% of employment, 35% of total income, and funding half of their respective county and school budgets through taxes and fees.

But an increasing amount of evidence suggests that these benefits are not distributed equally. As we noted in a memo in mid-2022, “within 5 miles of a nuclear power plant, counties have a mean percentage of Black residents 5.7% lower than in the surrounding counties. Within this same boundary, average incomes are almost $9,000 higher, and education levels are 6.4% higher than surrounding areas.”

In practice, the more dangerous aspects of nuclear energy, such as uranium milling and mining, have tended to harm marginalized communities the most. The Fastest Path to Zero initiative at the University of Michigan conducted a demographic analysis of fuel cycle facilities and found that communities around extraction facilities have a significantly higher number of Native American, Latino, and Hispanic populations, and higher levels of poverty than neighboring areas.

Advancing distributive justice for nuclear may be challenging. True justice will mean that communities share in the benefits of new nuclear technologies equitably, and that power providers and the government mitigate risks to the highest extent possible to ensure a less disparate range of outcomes. Communities must also be newly empowered to decide which energy technologies and industries they would like to support.

There are a number of frameworks that work to achieve these ends. Carbon180, in a report on siting carbon capture and storage facilities, suggests that community benefits agreements, co-created with project developers and communities, are one option to help communities advocate for project terms that may guarantee further benefits beyond the project. For more controversial and environmentally impactful facilities, such as with the consent-based siting process for nuclear waste storage discussed above, considerations of distributive justice grow even more critical.

Exploring Alternatives to New Uranium Mining

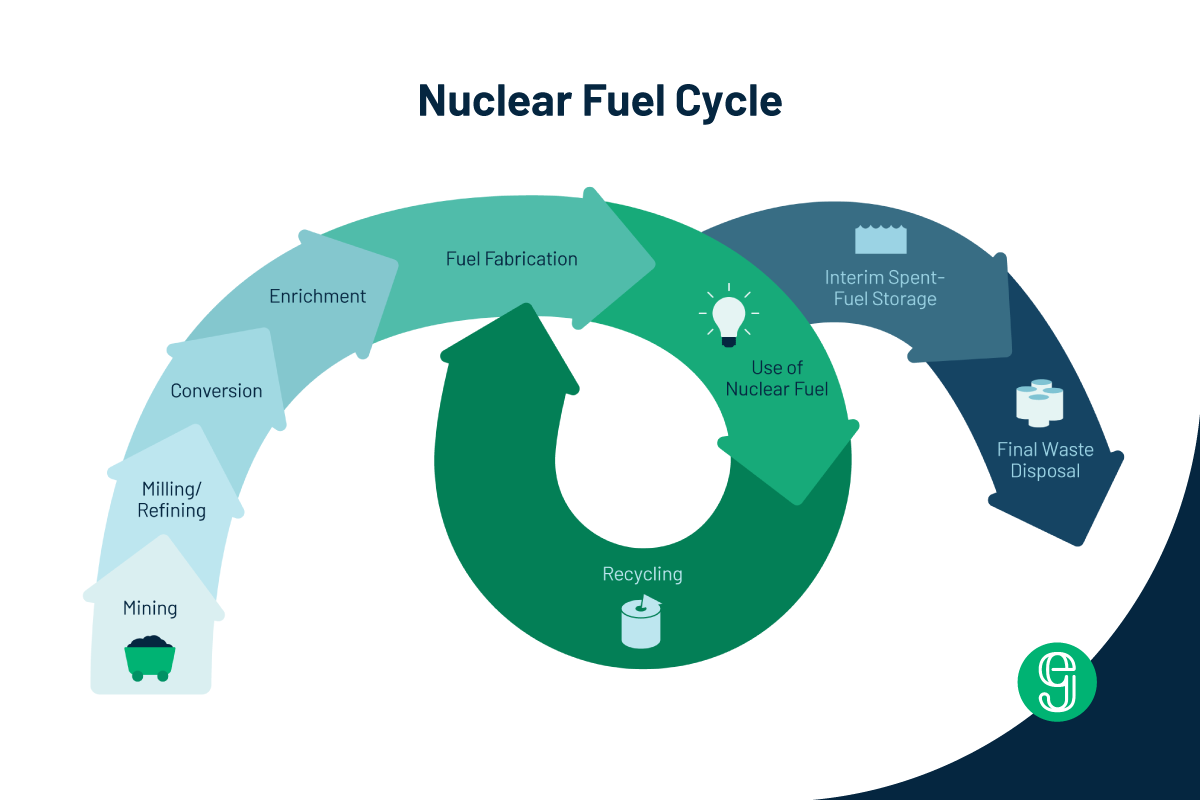

To advance nuclear justice, new uranium mining should be constrained to areas where there is strong community support. Federal policy should prioritize alternatives to fresh mining—such as reprocessing spent nuclear fuel, downblending weapons-grade nuclear material, uranium extraction in seawater, or re-mining abandoned mine waste.

Forming Community Benefit Agreements

State and community stakeholders, developers, and utilities can work together to establish community benefit agreements to come to a mutually-agreed, legally binding set of investments the developer commits to making in exchange for project support. The Energy Department’s Office of Minority Business and Economic Development has a guide for communities, states, and municipalities on how to form community benefit agreements for energy infrastructure projects.

Exploring Co-Management with Tribal Nations

Where tribes are interested, developers can explore potential opportunities to co-manage nuclear fuel cycle or power generation facilities with tribal nations. In a first-of-a-kind achievement, five tribes and the Biden administration in June 2022 agreed to co-manage the Bears Ears National Monument and work together to protect the area and traditional uses of the lands.

The Future of Nuclear Justice

In our conversations, some industry participants express concern that earning public trust and support for their technologies will take too long. But our understanding of the past and present of public sentiment toward nuclear mandates that the nuclear industry and the government work to see potential nuclear host communities as equal partners and co-developers in a mutually beneficial project. Developers must familiarize themselves with issues of nuclear injustice, undertake a process to understand communities’ values and economic or climate goals, and answer their questions in open and honest dialogue, to build trust toward a successful project. Otherwise, nuclear runs the risk of failing to change the prevalent perception as an industry that inconsistently and unevenly prioritizes public health and prosperity.

From our ongoing research and conversation, we find many actions the industry can take to expand public trust in nuclear energy. Some of these are procedural justice activities, including identifying and implementing strong community engagement practices before, during, and after new nuclear facilities enter into operation. As part of that practice, developers and utilities should accept when key stakeholders in a certain area ultimately say “no” to a new nuclear project. Some communities are more likely to be interested in nuclear energy than others, such as ones already familiar with hosting large energy infrastructure. For example, survey research from the Potential Energy Coalition finds a small premium in support for nuclear energy in communities with retiring coal plants.

Industry players can simultaneously move forward with new nuclear projects in communities that are more supportive of the technology while also taking other steps to broaden trust, such as supporting investments that advance nuclear justice on equal footing with technological nuclear programs and incentives. At a minimum, these investments should include increased federal funding for restoring former uranium mining and milling and weapons testing sites. Nuclear university programs, societies, and utilities can also work to increase the still-lacking diversity of the nuclear industry at every level.

State and federal policymakers can also work to facilitate more just and equitable outcomes for the public with nuclear energy. They can fund community-led or -involved feasibility studies into the siting of new nuclear reactors and provide grants or other assistance to local governments or community organizations that want to learn more about nuclear technology or participate in ongoing siting conversations. They can also explore ways to facilitate community ownership, commercial ownership, or joint ownership of new nuclear projects. Meanwhile, the Office of Nuclear Energy at the Energy Department can continue to support greater diversity of nuclear scholars and of scholarship into the social scientific dimensions of the technology, in order to fill research gaps into political, anthropological, sociological, and other underexplored aspects of nuclear.

On a final note, many of these injustices are not unique to nuclear energy. Mining for the lithium and cobalt necessary for batteries is increasingly under scrutiny. Conservation groups are concerned about the impact on sensitive ecosystems from large-scale wind and solar developments. And more renewables projects in the U.S. and Europe are facing strong opposition from local communities, with critiques of the siting processes as one of the main drivers. Nuclear faces unique historical issues linked to connections in its formative years with nuclear weapons production. But nuclear technologies also benefit from decades of examples to learn from. Ultimately, if the nuclear industry can develop just and equitable processes for siting new projects and fuel cycle facilities, it can share these lessons across the clean energy sector. Progressive climate activists are right: Clean energy transitions are inextricably linked to environmental justice, and we need to work together to ensure a healthy, equitable future.

.png)

.png)

%252520(1200%252520%2525C3%252597%252520800%252520px).png)