Khalil delves into the profound impact and lasting legacy of the Megatons to Megawatts program, a pivotal disarmament agreement between the U.S. and Russia.

.png)

Click here for a pdf of the explainer

At the end of the Cold War, amid the dissolution of the USSR, the Russian Federation possessed ~35,000 nuclear warheads, many of them located in newly independent nations. The decommissioning of Soviet nuclear weapons under the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty of 1979 and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) of 1991 concerned U.S. scientists and politicians. Would these nations properly store and protect these weapons, or would excess material from Russia’s stockpile and decommissioned weapons lead to nuclear proliferation from rogue actors? Would an overabundance of Russian uranium from decommissioned warheads flood the U.S. market and drive down uranium prices, disadvantaging American nuclear material producers? Ultimately, a policy intervention called the Megatons to Megawatts program served to reduce the Russian nuclear weapons stockpile, generate 10% of U.S. electricity for 20 years, and strengthen diplomatic ties between Russia and the United States.

At the end of the Cold War, amid the dissolution of the USSR, the Russian Federation possessed ~35,000 nuclear warheads, many of them located in newly independent nations. The decommissioning of Soviet nuclear weapons under the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty of 1979 and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) of 1991 concerned U.S. scientists and politicians. Would these nations properly store and protect these weapons, or would excess material from Russia’s stockpile and decommissioned weapons lead to nuclear proliferation from rogue actors? Would an overabundance of Russian uranium from decommissioned warheads flood the U.S. market and drive down uranium prices, disadvantaging American nuclear material producers? Ultimately, a policy intervention called the Megatons to Megawatts program served to reduce the Russian nuclear weapons stockpile, generate 10% of U.S. electricity for 20 years, and strengthen diplomatic ties between Russia and the United States.

To reckon with market and proliferation concerns, MIT professor Thomas Neff in 1991 suggested the concept of downblending the uranium in Russian Federation weapons into fuel for commercial nuclear plants. The U.S. Department of Energy later built upon and implemented Neff’s proposal. The agreement established terms between the U.S. and the Russian Federation that stipulated the down-blending of ~500 tons of high-enriched uranium (HEU) from decommissioned Russian warheads and selling low-enriched uranium (LEU) to the U.S. for a period of 20 years. By purchasing LEU, the U.S. could fuel its growing commercial nuclear industry while reducing the risk of unsecured nuclear materials. The U.S. government appointed the U.S. Enrichment Corporation (USEC), a federally-owned entity, as the proprietary in potential contracts for purchasing enriched uranium to facilitate this agreement.1 In 1995, Congress privatized USEC so that the U.S. could create a profitable market for the natural uranium obtained through the agreement while encouraging the continued decommissioning of Russian nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, Russia designated the state-owned subsidiary Techsnabexport (Tenex) for the sale of enriched uranium.

To establish the Megaton to Megawatts agreement, the U.S. and Russia needed to set an agreed-upon price for the provided LEU. The initial pricing of uranium at $13/lb under the 1992 Suspension Agreement and the global prices stagnating below $10/lb elevated concerns that Russia would be unable to compete in the American uranium market.1 To alleviate these concerns, legislators amended the 1992 Suspension Agreement that restricted the volume of uranium exports to create more favorable terms for Megatons to Megawatts. These terms established a system of equivalent exchange for the natural uranium used in down-blending HEU to LEU.

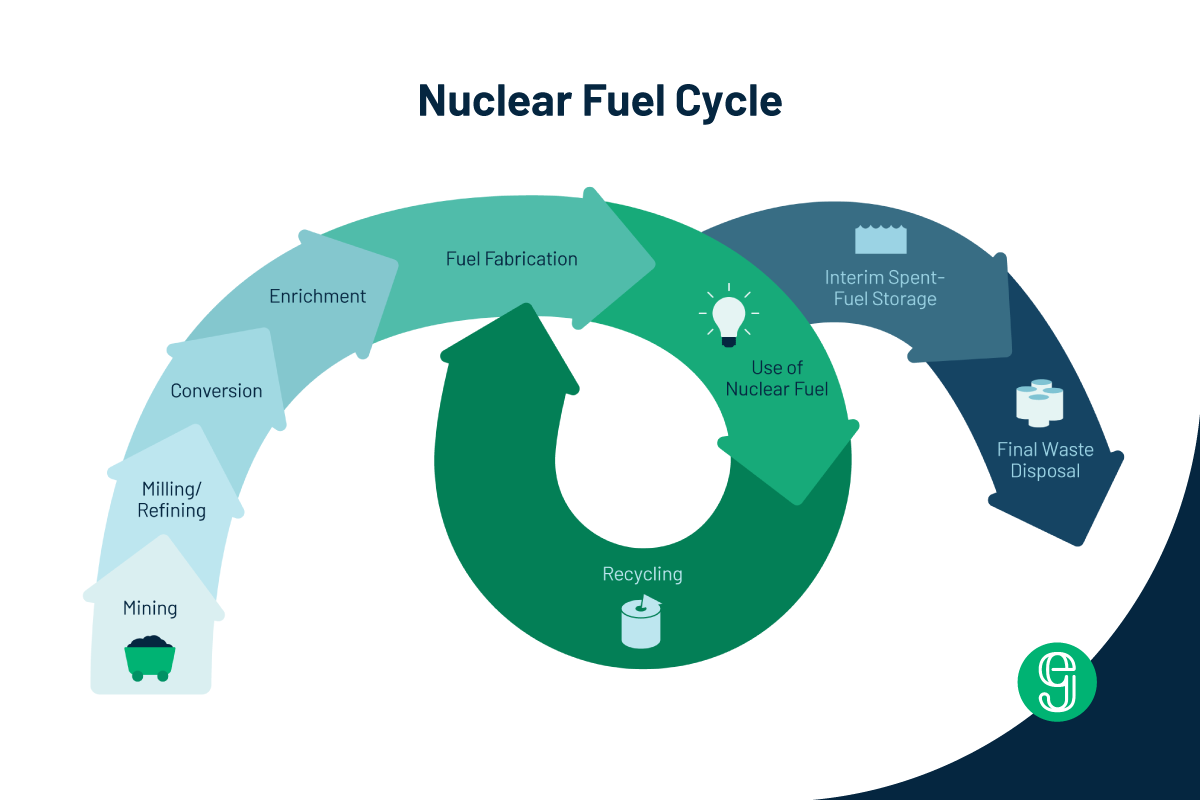

The final agreement specified that Russia would collect HEU from Russian warheads. The collected HEU would then be downblended, and the LEU produced from the downblending would be sold to the U.S. via USEC. Natural uranium is required to dilute the HEU into LEU during the down-blending process. USEC would later sell to Russia an amount of natural uranium equivalent to the amount used during the dilution of the HEU.

After the agreed-upon period of 20 years, the Megatons to Megawatts program concluded in 2013 after supplying 10% of American electricity from 1993 to 2013. The agreement eliminated nuclear material equivalent to ~20,000 nuclear warheads and generated nearly half of all commercial nuclear energy produced within the United States during those 20 years. It represented a significant victory for global disarmament and nonproliferation advocates and provided the basis for other potential agreements that could reduce global nuclear stockpiles.

The Megatons to Megawatts program initially spurred additional cooperation toward disarmament between the U.S. and Russia that has not succeeded. The programs laid the groundwork for the Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement (PMDA), a 16-year agreement between the U.S. and Russia to dispose of and convert at least 34 tons of weapons-usable plutonium into mixed oxide uranium-plutonium (MOX) fuel. Construction on the MOX facility at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina began in 2007 after the signing of the PMDA. However, the project suffered from numerous delays and financial issues. Construction ended in 2019. Russia suspended the PMDA in 2016, citing U.S. economic sanctions and increased NATO presence in Europe. The failure of the PMDA and the construction of a domestic MOX facility has hindered the movement toward global disarmament.

Despite these setbacks, the U.S. has an opportunity to establish a spiritual successor to both Megatons to Megawatts and the PMDA. As the U.S. looks to promote energy security, policymakers could implement a strictly domestic program that builds upon the Megatons to Megawatts concept by downblending U.S. warheads into usable nuclear fuel. Revitalizing Megatons to Megawatts could foster domestic steps toward nonproliferation while supporting carbon-free electricity production.

References

1) Kaoutzanis, C (2011). Megatons to Megawatts: mega-player of u.s nuclear enrichment. Georgetown International Environmental Law Review, 24(1), 1-22

2) Neff, T. L. (1991, October 24). A grand uranium bargain. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/24/opinion/a-grand-uranium-bargain.html

3) Brumfiel, G. (2013, December 11). Megatons to megawatts: Russian warheads fuel U.S. Power Plants. NPR.

https://www.npr.org/2013/12/11/250007526/megatons-to-megawatts-russian-warheads-fuel-u-s-power-plants

4) Congressional Record." Congress.gov, Library of Congress, 13 September 2023, https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/volume-141/issue-73/senate-section/article/S6165-1.

5) Megatons to megawatts program will conclude at the end of 2013. Homepage - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (n.d.). https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=13091

6) Megatons to megawatts program will conclude at the end of 2013. Homepage - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (n.d.). https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=13091

https://www.powermag.com/20000-nuclear-weapons-later-megatons-to-megawatts-program-complete/

7) https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/military-warheads-as-a-source-of-nuclear-fuel.aspx

8) Schumann, A. (2016, November 3). The end of the Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement: A dark cloud with a silver lining. Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation.

https://armscontrolcenter.org/end-plutonium-management-disposition-agreement-dark-cloud-silver-lining/

.png)

.png)

%252520(1200%252520%2525C3%252597%252520800%252520px).png)